The 787 Program

The first plane in the 20xx program was to be a replacement for the 767 size plane, but with a twist. It would be suitable for a lot more types of routes, including very long ones, well beyond the range of the 767.

The program, which was the 20xx program's airplane number one had several goals.

1. Move toward reshaping the industry so that suppliers were more independent and in continuous design mode.

2. Take our progress in lean manufacturing to the next level.

3. Build a great airplane that took advantage of the many advances in technology since the 777.

As with all aerospace programs, the nature of the beast is basically inventing on a schedule.

The core competency of The Boeing Company prior to its takeover by the idiots from GE and its subsequent demise, was complex systems integration. That's what we did, and what made us who we were. This was true, no matter what part of Boeing one is talking about.

Designing something that flies with a mission is a battle among the many engineering disciplines involved. There is not enough capacity in terms of either weight or space for everything that has to to on the air vehicle. So everything that the engineers are designing has to be done in a teaming relationship so that as many components as possible can do more than one thing. For example, a wing is structure that provides a shape that can fly, it is a fuel tank, it is an engine support, it is a main landing gear support, it is a guideway for hydraulic lines and wire bundles, it is a support for a bunch of hinges for the moveable surfaces, it is a platform on which technicians stand to perform certain maintenance operations, It's a reflective surface for radar imaging, it is part of a complex lightening management system, it is even a platform for the paint job (livery) that the customer wants on it. And that is just part of what it has to do. Other parts of the plane also have long lists of things they have to do and be, and each of those things involves different engineering specialties. Bringing all of these things together on schedule, on budget, within the weight targets, and with the range and fuel burn specifications is always difficult. The old Boeing of the totem was good at doing this. The Boeing of the swoosh is simply incapable of even coming close.

The secret sauce to making this work is a combination of the very best talent one can find, and creating a working environment that enables them to perform at their very best. Each team member has to be bringing their passion to the the task at hand. Aretha Franklin sang it so well. It all starts with "R-E-S-P-E-C-T" and "Find(ing) out what it means to (each person on the team)."

When the Toyota workforce walked out the door in 1949, that was the crux of their demands. They wanted the entire top leadership of the company changed, and a new attitude of shared destiny before they would return. Their demands were met, and they haven't walked out since. What they have done is taken an impoverished wreck of a company that was devastated by the destruction of war and built it into one of the finest producers of quality transportation equipment on the planet. The old Boeing had that. The folks from GE threw it away.

An open, trusting, honest, and speedy flow of information environment is fundamentally critical to designing something that flies. Without a culture that demands and nurtures these qualities, the engineering job simply cannot be done successfully. Even with all of those attributes, one has to be very careful. After all, stuffing an aluminum or carbon fiber can full of people and shooting it through the air at 600mph is a fairly outrageous proposition to begin with. Making it safe, practical, and actually enjoyable requires extreme focus on the task at hand. There just isn't any room for turkey strutting liars in such a business.

The 787 program seemed to start out ok, although there were some warning signs even in the very early stages, before full scale engineering development began. First, the product had to be defined. How many engines would if have, where would they be mounted, what were the target performance characteristics in terms of payload, range, fuel burn, maintenance cycles, special equipment to support it, training parameters, and basically everything that defined what the plane had to do physically and economically.

Only a couple hundred people typically work on the early product definition. Once it is nailed down, a board presentation has to be made to get buy-off on offering it for sale and bringing on a few thousand people to actually make it happen. At program peak, there could be over ten thousand people on it in Boeing alone, and several times that many in the supply chain. Plus, for 20xx program airplane #1, we had to work with that supply chain quite dramatically more closely than ever before. We had to coach them through the process of becoming more independent, and we had to learn what needed to change the way we did things inside Boeing to make that possible. Initially, and then adapt to the new reality ourselves. Our program costs would be higher, but in the long run, this would set us up to be much more efficient.

It didn't happen.

Probably the first thing that started to go wrong after the program was injected with a bunch of people from McDonnell Douglas who had been trained to be like the GE idiots, was their introduction of what came to be called the watermelon charts. If you want to see Alan Mulally lose his cool about something, try keeping something a secret that needs management attention. One of his favorite lines was: "You can't manage a secret." And the most important thing management needs to know is what needs their attention.

One of the most fundamental jobs of a manager is resource allocation. When some one or some team needs some help, management job one is to find a way to get it for them. However, in the GE way of doing things, job one was to tell the boss that everything was on track and no help was needed, even when it is. That's called lying, and my were they ever good at it.

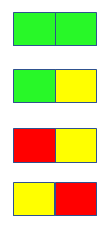

The Boeing project and program methodology uses a tool known as a stoplight chart. When reporting on your pieces of the activity, each item is on its own line on your status charts, and there is a two part box next to it, with each part shaded either green, yellow, or red. The left half is the condition it was in during your previous report. The right half is what you are reporting now. So the trend is also instantly visible.

The colors can mean slightly different things, depending on the nature of the item. If it is a complex integration task, where the solution is being discovered as a part of the activity, you might not go to green until you have a high level of confidence that the final solution has actually been discovered., So you might be red or yellow until very near your committed delivery date. On the other hand, if the task is simply a repeat of a well known activity and you are on schedule, then it might be ok to show it green, even though one is just getting started.

Red might mean that you don't have a clue as to what the final outcome is going to look like exactly, but you may have a high level of confidence that your team has what it needs to get there. That said, if you stay red for too many report-outs, the chief engineer or program manager may decide that it's time to have a special attention meeting on your item so they can better understand the situation. The point, is that having a good feel for how things are going is the only way that the more senior managers can redirect resources and make sure that help is being provided where it is needed.

The worst possible thing one can do is report your status as green when it is really red. Charts like that are called "watermelon charts," as in green on the outside and flaming red on the inside. Pitching a watermelon chart is considered to be telling the boss a lie. And, it is in effect, sabotaging the efforts of everyone of the program. You really don't want to do that, at least you didn't in the old Boeing of the totem. The swoosh guys and gals? Well, that's another story. And the 787 program, right from the vote by the board to commit to full scale engineering development (FSED), was filled with people who pitched watermelon charts as a matter of routine. They did this because starting with the CEO, it was made clear that you only told the boss what they wanted to hear. Nothing else was acceptable. Your task was to make your numbers, meaning your budget numbers. The details of designing and building things that fly? They just weren't interested in that stuff.

In the GE culture of greed, they believe that the return on stockholder's equity is the only thing that is really important. The fact that we were an aerospace company was secondary. One often felt that the GE trained folks believe that designing and building things that fly is boring. It's that complete Wall Street stupidity that "all companies are the same." Also, and this part would be funny if it hadn't been so destructive, the GE trained folks, did not understand the basics of accounting, and I'm talking Accounting 101 stuff. That's the generous interpretation of their behavior. If they really did understand the fundamentals of accounting, then they deliberately chose to misrepresent them. The details of this are covered in a separate section. But suffice it to say here, that whether they simply didn't understand basic accounting, or were deliberately misstating it, they got it horribly wrong.

The result of these two failures (i.e. the destruction of the passion for excellence that drove the old Boeing of the totem, and getting the accounting wrong, which are not really separate times), was that instead of the 787 being the Airbus killing product that it could have been, and just the first plane in an all new family of amazing Boeing jets, it has been a financial disaster. Because of a failure to execute on the 787 Program, by 2018 The Boeing Company had been driven into bankruptcy. Yes that's true. Check the published balance sheets. Click here to see them, and expand the "Liabilities & Shareholder's Equity" section so you can see the bottom lines.

There is one other part of the 787 story that is more humorous. That's the saga of the so-called Sonic Cruiser. It is also in another section on this site.